Filmmaker, Mother, Activist: Madeline Anderson, in Her Own Words

Interview between Rhea L. Combs and Madeline Anderson

Image courtesy of National Museum of African American History and Culture

I first learned about Madeline Anderson (b. 1927), primarily through her work on the public affairs news program Black Journal, when I was a graduate student conducting research on African-American cultural production. As I recall, her name was a footnote in an essay; there was not much information beyond a credit line. At the time, I was seeking to identify pioneering female filmmakers since the field of study is often so male-dominated. I was determined to find out if there were women working behind the camera as well. As my research expanded, I learned about Zora Neale Hurston’s anthropological film work and Kathleen Collins’s Losing Ground, as well as the work of the women who attended the University of California, Los Angeles’ film school—including Julie Dash, Zeinabu Irene Davis, and Alile Sharon Larkin—and quite a few others. Unfortunately, the fact remains that the directorial work of African-American female filmmakers is often overlooked, although there is has been a sustained history of women pushing open the doors of cinematic opportunity. And Madeline Anderson, the first African-American woman to produce and direct a televised documentary film and a syndicated television series, has been at the helm—despite only receiving passing recognition in an obscure essay.

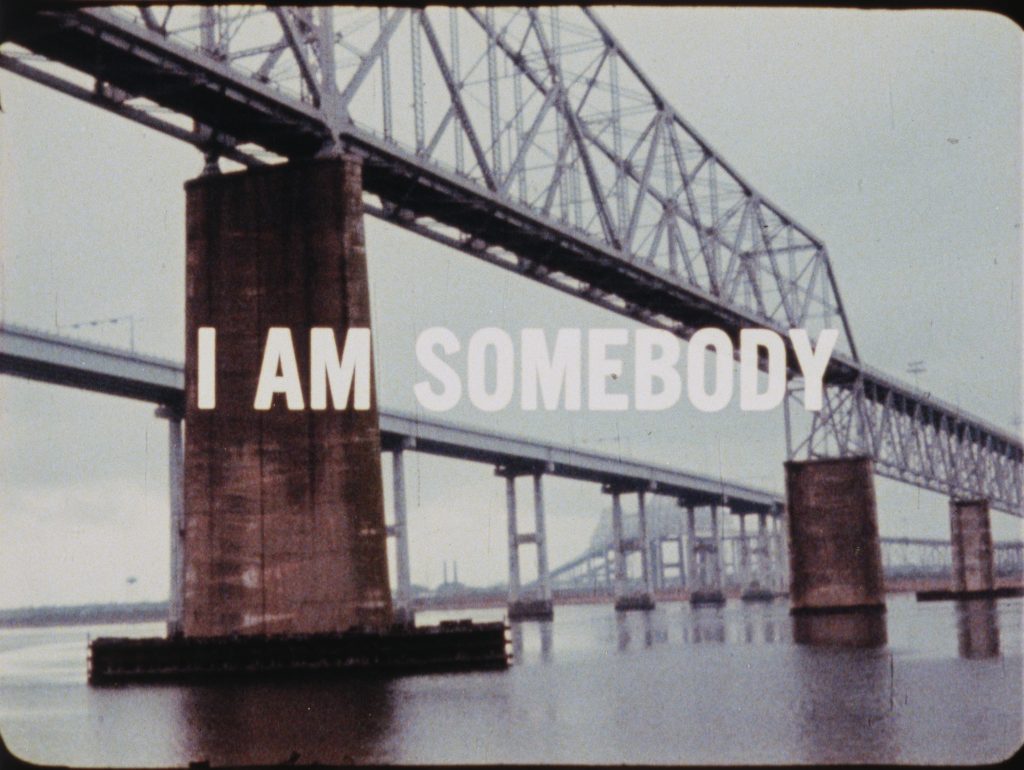

Having the unique opportunity to work with Icarus Films to preserve and collect Anderson’s early documentary works, Integration Report 1 (1960), A Tribute to Malcolm X (1967), and I Am Somebody (1970), has been very important to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture because it supports the mission of the museum. Working with Icarus Films to restore Madeline Anderson’s films and being able to share the triumphant story of this trailblazer reinforces the institution’s commitment to telling the American story through an African-American lens. And it is quite apparent, after spending time with this dynamic filmmaker, that she has had a clarity of vision and a fierce determination since her days as growing up in Depression-era central Pennsylvania.

On February 23, 2016, I sat down with filmmaker and editor Madeline Anderson in her Brooklyn, New York home to talk about her upbringing, her career, and her extraordinary life as a working wife and mother of four. Anderson detailed the challenges of attempting to create a work-life balance—particularly for an African-American woman—and what motivated her to make movies in the first place. Talking to the clear-minded, bright, and witty octogenarian, whose boundless energy seems to defy her chronological age of almost ninety, was equal parts illuminating and inspiring. Below is an excerpt from our interview. —Rhea L. Combs

RHEA L. COMBS: Can you tell me about your background growing up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania?

Everybody in town ridiculed the people that lived on Barney Google’s Row because we were all poor. I would say that people migrating from the South who didn’t have relatives to come to, who didn’t have a job, and were looking for housing lived there because it was the cheapest housing available. This is how we landed there. My mother came from Virginia, my father from North Carolina. They were both young farm workers with little or no education. My mother had two older brothers who lived in Lancaster, and she came up to live with one of them. She was the youngest daughter of the family. While in Lancaster, she met my father and they got married. She worked as a domestic, and he worked in a stone quarry as a day laborer. This was the best housing that they could afford at that time. We lived on Barney Google’s Row until I was 12 years old. Later, my parents made more money and we were able to move out, but I never escaped the taint of living on Barney Google’s Row.

MADELINE ANDERSON: Well, we lived on the wrong side of the wrong side of the track. We lived in the poorest housing in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. It had a very fancy address—720 East End Avenue—but everyone knew it as Barney Google’s Row. It was called this because of the row of little houses. Each house comprised of three rooms, a backyard, and a big alley. There was a big field in the front of us where blue-collar white people lived, but we lived in the back. A short man with large glasses who looked like the character Barney Google owned the row of houses. The owner’s name was Cohen, but looked like Barney Google so the area was known as Barney Google’s Row.

RC: How did living in this area impact your education?

MA: Interestingly, I had the best education of any black child in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. All the black people in Lancaster lived in the Seventh Ward, but we lived too far from the main area—where all the prominent black people lived and had built a school. Because I was on the outskirts there were not enough black kids where I lived to build a school only for black kids, so I went to integrated schools.

I was born in 1927, so in the 1930s, during the Depression, the poor black kids from Barney Google’s Row attended an integrated elementary school and received the best education with good teachers. Ironically, we had opportunities that the majority of black kids in Lancaster didn’t have, simply because of where we lived.

RC: When and how were you introduced to the movies?

MA: Every Saturday my oldest brother and I would go to the movies and stay all day. There were two movie houses in our area, but one movie house allowed us entrance. Technically, we could attend both theatres, but in one movie house blacks had to sit in a certain section. Fulton Theatre, all the kids, black and white, went there. Each weekend my mother would scrape together—that’s what she called it, she’d say, “I’m scraping together some money for you guys to go to the movies.” She used to give us a little brown bag with an apple, and a piece of Mary Jane candy. That was our meal for the day.

When we went to the movies, we would see Tarzan. That was one of the favorite movies they showed; and after a while, I began to think about the Africans. When we got home, we would reenact the scenes. I always wanted to be the director, but there was opposition, of course, so we would choose different roles to play. No one wanted to be the Africans and they would say, “Oh, the Africans are not smart. The white man is always smarter.” “The white man takes their jewelry; they take everything that they have.” Nobody wanted to be the African, so I said, “I’ll be the African,” in order to then take turns and also be the director; but then after I played the African for a while, I started to think: How come the Africans were stupid? They had land. They were kings. They knew how to rule. Something was wrong with this picture, so I began, on my own, going to the town library, not the school library, which was about a mile and a half from my house. I started to read about black people and their accomplishments. I read about people like George Washington Carver, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth. One day I thought to myself, “I’m going to tell other people about the black people who do things,” and so I started to talk and tell people about black people and their accomplishments.

RC: When did you know you wanted to be a filmmaker?

MA: I knew I wanted to be a filmmaker from a very young age. I used to make those little flip books and I learned about movement and light, and I loved it. I drew little stick figures and made little flip books, so I knew I wanted to be a filmmaker. But I also wanted to please my parents. I wanted to be something they would be proud of. They were both from the South and being a teacher was an honored profession, so I went to school to become a teacher.

RC: Where did you go, and what was that experience like?

MA: I went to Millersville Teachers College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. I was the second black person they had ever admitted to the school. I graduated from high school in 1945 and started school immediately after. There was one other African-American woman there, but she was in her senior year. I went there because I did well in high school. I later found out that some of my high school teachers from McCaskey High School were instrumental in my being admitted to Millersville.

Keep in mind what the world was in 1945; this is after the Second World War. When I entered the school, there was an influx of young, white males who would ordinarily have went back to working on the farms, but because they had seen the world, they had seen that there was something better for them to do, and so they went to college and a fair number of them went to Millersville. There were two colleges in town at that time—Franklin & Marshall, and Millersville. Millersville was the Teachers College. I was bullied by these young men. I had two white female friends who I knew from high school. They both did not agree with how I was being treated, and they supported me as much as they could, but there were limits to how far they were going to go.

I was bullied at first with words but then one day, someone threw a piece of paper at me. I thought to myself, “Huh?” I told my father. Millersville was three miles from where I lived and I caught a bus there every day. My father said he would come with me to the school, so he rode on the bus with me for a while. But then I was afraid that my father would get into trouble because they didn’t stop the bullying. I was afraid that it would get physical, and I would be hurt, and I was afraid for my father. He had a good job. I didn’t want him to go to jail. The staff at the school knew it, because my biology professor called me aside one day and he said, “I know what’s going on.” He said, “I can get you a scholarship to Tuskegee University, the historically black college.” I thought about it, but I didn’t fit into the black bourgeoisie in Lancaster and thought the negative experiences I had growing up would be the same if I went there. With the constant threats mounting, I told my parents I would finish out the year, but not return. They were very sad because I would have been the first one in my family to go to college, but I refused to accept that ongoing hostility.

I got a job shortly after I dropped out of Millersville State Teachers College at Radio Corporation of America (RCA), who built a factory in the town. They hired black people in the factory, but only if you had a high school education. This was not required of others, but blacks had to have a high school education. I had a high school education and a year of college, and still had to take several tests. After I passed all the requirements, I worked at RCA and made a fairly good salary. But then the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers of the World came to Lancaster and organized the factory. I joined the organizers and we went out on the picket lines. I worked in the union office and I handed out leaflets. Management said the people who were on the picket lines would not be let back into the factory and would lose our jobs. That was not true; we were re-hired, and that is when I learned the importance of being in a union. I worked at RCA for two years and I saved my money. I applied to New York University (NYU) and received a partial scholarship and came to New York.

RC: Did you attend NYU for filmmaking or teaching?

MA: Teaching. Even though I wanted to be a filmmaker, I didn’t have any encouragement in Lancaster. I had no role models and my family and friends would laugh when I told them wanted to be a filmmaker, but I didn’t give up my dream.

RC: What was life like for a young African-American woman coming to New York City by herself in the early 1950s?

MA: I had to work. The partial scholarship just paid for my books. So I had various jobs, I worked at the fast food chain Nedick’s so I could eat. I worked on Fifth Avenue, which was not far from NYU, as a proofreader. I had an aunt who lived in Brooklyn, so I initially lived with her when I came to New York; but shortly after I got here, less than a year, she became sick and passed away. Her husband remarried immediately and I had to find a place to live. I knew the part-time jobs would not pay my rent. I saw a bulletin board for students at the school and there was an ad for a babysitter/boarder to work with Dr. Eleanor Leacock. I went for an interview, got the job, and received room and board. Her husband was Richard “Ricky” Leacock, the famous, renowned documentary filmmaker. I told them I wanted to be a filmmaker and they were so excited and supportive of me. Whenever Ricky came home from being out on location, he and the crew would review dailies in the basement and invite me to come look at the dailies. Over time, I got to know people and they would say, “This young black woman wants to be a filmmaker, and she wants to make films about civil rights.”

In that supportive environment, my dream of being a filmmaker was nourished. I got to know the filmmaking process like shooting, being on location, and looking at dailies. Eventually however, I met my husband, got married, and left the Leacocks’. Ricky Leacock ended up creating a company called Andover Productions and he hired me to be his in-house production manager. That was the beginning of my career in the industry.

As a production manager, I learned all the aspects of filmmaking. I already knew about going on location and about the necessary equipment and film stock; I knew what kind of crew you had to have, because that’s what I did as production manager. Ricky worked on location with other filmmakers like Willard Van Dyke, D. A. Pennebaker, Shirley Clarke, and later on, the Maysles brothers. I got to know all of these extraordinary filmmakers. They would look at films, they would critique films, and invite me to come and participate, so I ended up having this incredible informal education by some of the brightest minds in filmmaking.

RC: Is it this experience that prompted you to become a documentary filmmaker?

MA: I wanted to make films to teach. I wanted to tell people about the accomplishments of African-Americans and then as I became politicized, I wanted to tell people about the struggle blacks were facing to become equal citizens of the United States. I never wanted to make a Hollywood film—although, later on in my career, in the 1970s, I was offered a job to direct one. A black businessman and his wife wanted to make a beautiful little film about a love affair between cultures, like a West Side Story film. I was ready to do that but it became clear nobody was going to buy a black love story without it being a black exploitation film. I had no desire to give my life to making an exploitation film. Although there were a lot of negative feelings about black exploitation films, I recognize it also opened up the door for black filmmakers; I just was not attracted to that type of storytelling.

RC: How did your informal training impact your career?

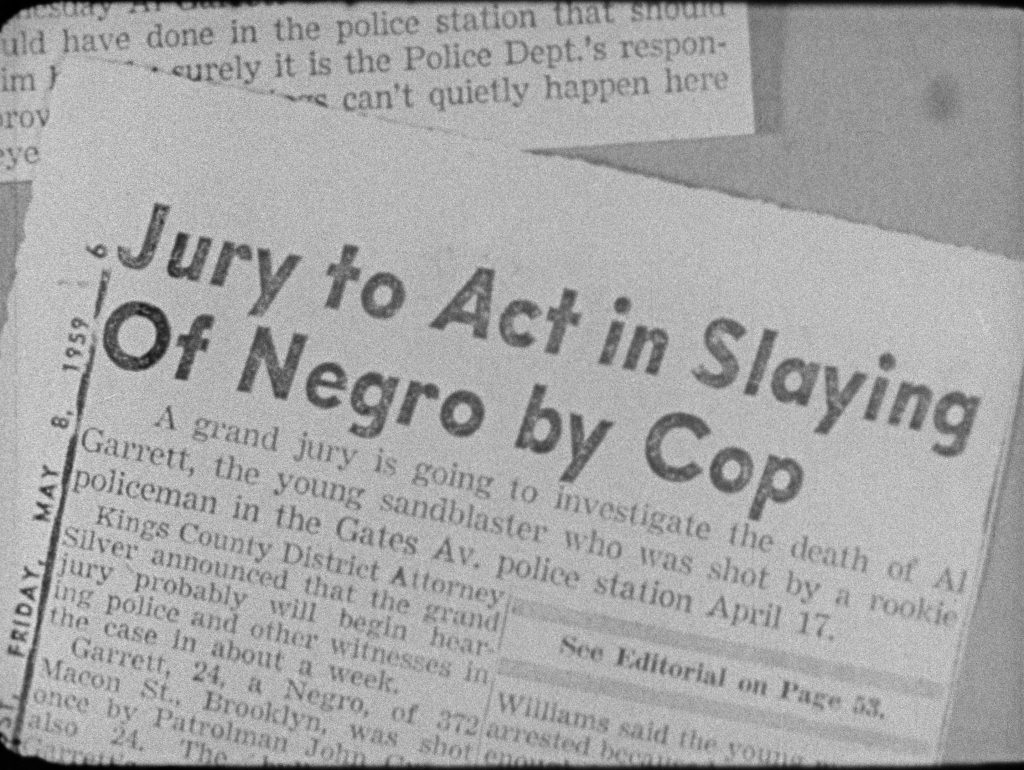

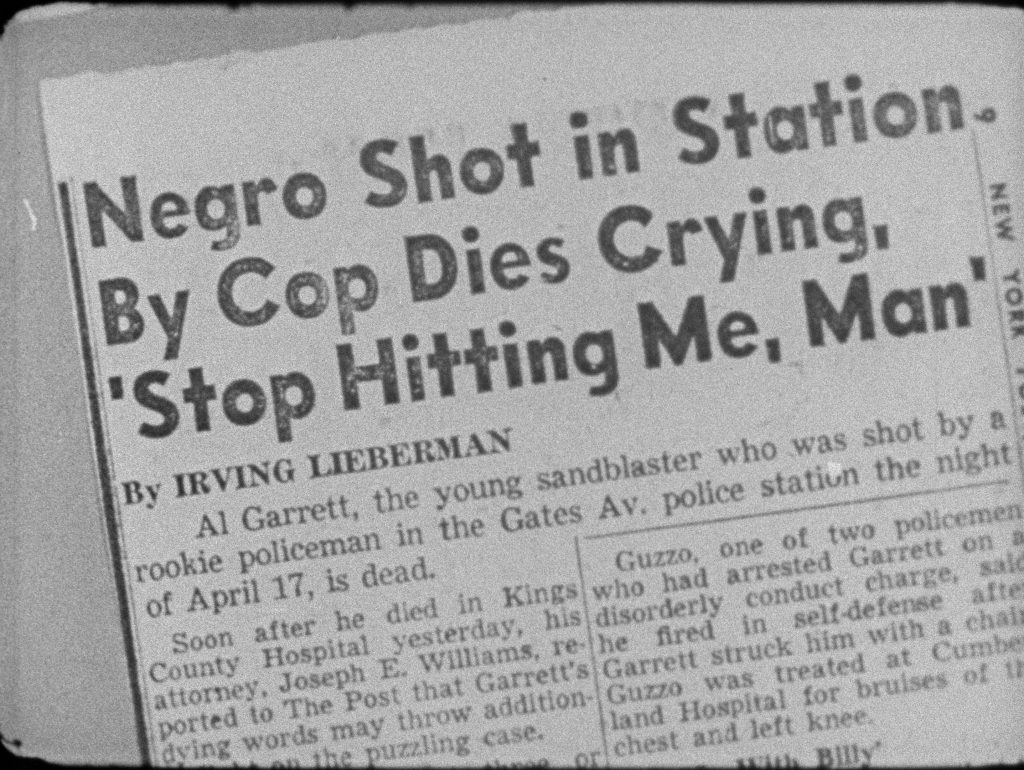

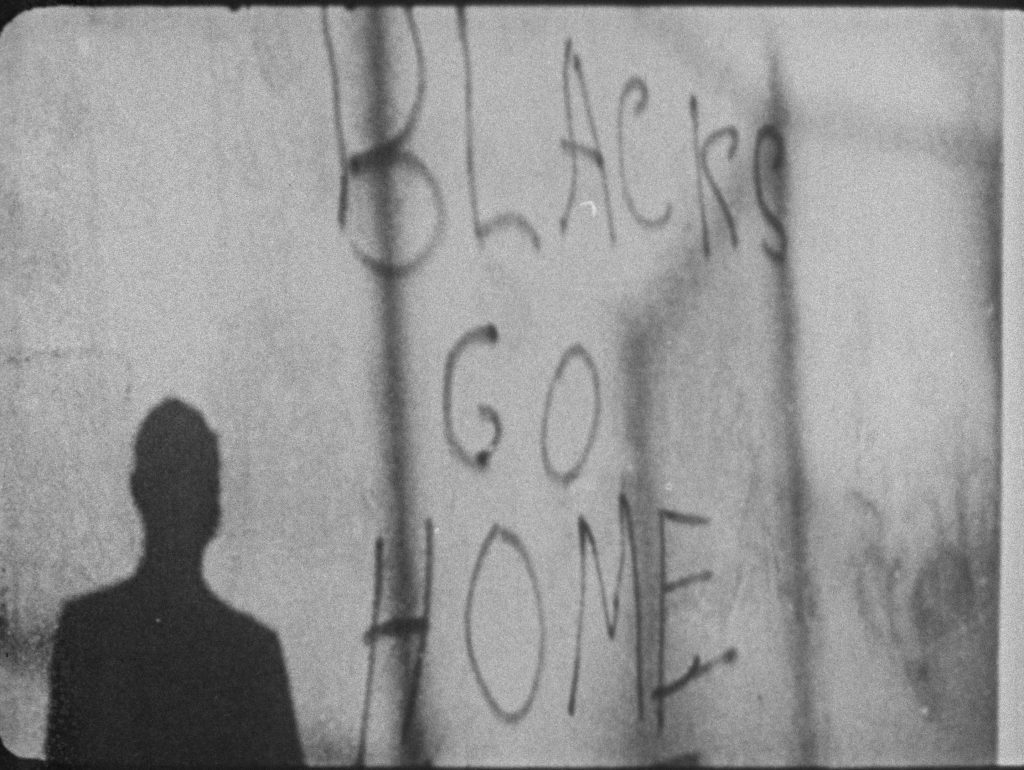

MA: After I worked with Ricky for two years as an in-house production manager, Ricky and I thought I was ready to make a film. Through Andover Productions, and using most of my salary, I directed and produced Integration Report 1. That was the first film I did. This is significant because I was the first black woman to produce and direct a documentary film. Secondly, the crew was all black males who were in the union. The cameraman was in the cameraman’s union. The soundman was in the soundman’s union. We didn’t have money for any electrician, so the camera people did the lighting. They were all older than me, but they were all very kind and supportive of my project and wanted me to succeed. It was at this time that I devised the methodology for how I would make films, because I knew from experience that I was never going to get a big budget to make a film. I had to figure out how could I make a low-budget film, but an effective film. This is what I devised: When I could get to the location, I would go on location; but when I couldn’t, I would go to the film library and get the newsreel footage to connect my documentary location shooting. And that is the methodology of how I made all of my films, starting with Integration Report 1, Malcolm X, and I Am Somebody. Those are my three major films. The other body of work that I did is children’s films for television.

RC: What inspired you to have this be your first film?

MA: My inspiration was to make films that would show that black people were fighting—were achieving, were fighting for their freedom. Too often people thought, erroneously, that black people were not interested enough in fighting for their freedom. I was on the picket line when I was 14 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. I was a junior member of the NAACP. Now, you couldn’t join until you were 16, but I was 14 on a picket line outside of the Brunswick Hotel, a business that we could not eat in. When I grew up in Lancaster, black people could not eat in restaurants downtown. We could shop in Woolworths, and they had a lunch counter, but we couldn’t eat there. If we wanted to go downtown and stay for hours, we had to take our food in a brown bag. If we went into a store, we were under surveillance. People followed us around and looked at us to make sure that we weren’t going to steal anything. There was an attitude that black people were not worthy of being free and being treated equally. I wanted to show that we were a people of accomplishment who were fighting for our rights. I did not just want to teach it, but wanted to record it so that you could see it and believe it. Because sometimes you can read a book and people would say it’s not true, or you could tell somebody something, but I felt if you saw it then maybe you had a better chance of 100 percent belief.

When I found out that there was no interest in funding a film like Integration Report 1, I had two choices—not make films, which was ridiculous, or figure out how I could. I knew I wanted to have a greater part in controlling what I did. I knew what the footage would look like, but I wasn’t in control of the editing. That’s where the film really is made, in the editing room. Moreover, I just loved looking at film from an early age. You know, like from the close-ups and the things that caught you and held you, so I wanted to become an editor. This was a daunting idea, because in order to get into the film editing union, your father had to be an editor, you had to be a man, and you had to be white. However, knowing what I wanted, I started at the bottom. I knew people and Ricky [Leacock] knew people. I got into an editing room as an apprentice. An apprentice keeps the film in order as the dailies come in. The apprentice gets it and takes it out of the box, labels it, and identifies it. Most of the time you have to wind the film, too. Since I had already made a film, I didn’t apprentice for long. Because I knew people, I also got jobs outside of the union. A lot of editors worked outside of the union to make extra money. This was called the edit underground and was dangerous work because you worked with people often making their first film, and who did not want to pay properly.

Nonetheless, this work allowed me to keep a hand in the union. I got a job with Shirley Clarke while she was making The Cool World. Shirley knew me because of Ricky Leacock and Integration Report 1 and because the woman who edited my film, Zina [Voynow], was also a friend of Shirley’s. Shirley hired me to be the script clerk, the person who worked on the continuity, for The Cool World. She took a big chance, because I had never done it before. For her I was doing continuity and keeping the script notes, and doing other things. When we went into the editing stage, she offered me a job to be her assistant and Hugh Robertson’s assistant. Hugh was in the union and it was because of him I got an application to the union. Since a recommendation was another requirement, he took a chance with me and recommended me for an application.

Even though I had an application, I was initially denied admission into the union. In addition to being a man, you had to have worked consistently for a year and a half before the board would review your application. I had worked in three production houses, and I made it up to 17 months. I thought that would be close enough, but they said no, it had to be 18 months.

Of the one thousand union members, ten of them were Caucasian women, and one African-American woman, Hortense “Tee” Beveridge. Tee was a new member of the editors union. A couple of women who knew I was trying to get into the union called me to have lunch and asked me to wait to get in the union because Tee had just gotten in; and because there was a recession in New York at that time, the film industry wasn’t in great shape. They thought my membership would be a burden to Tee, however I didn’t see the relationship and I refused. Tee was a wonderful editor but she did car commercials. I was not interested in doing commercials. I wanted to make documentaries. I talked to Tee about it, and she didn’t see the conflict, either. I called the National Labor Relations Board, and was going to sue. I presented my case, and they took it. The union was not in good shape at the time and didn’t want any bad publicity, especially from a black woman, so they let me in the union.

RC: How did your life change once you were in the union?

MA: I was able to get regular work. I went to work for NET. It was called NET at that time—now it is WNET—and I worked there for seven years as a film editor. Starting as an assistant, and then becoming a full editor, and having some other experiences along the way. I recall I was an assistant editor on this film about black women who had started the welfare rights movement in Detroit, and Zina was the editor. I got a phone call on a Sunday night from the producer of the film asking if I could I come to Detroit and be there for work on Monday morning? I said, “No. I have children. I can’t do it.” And then, I hung up and I told my husband he said, “Of course you’re going.” I said, “Wow. What?” So, I got on that plane and went to Detroit, but I also said to them, “I want a credit. What credit can I get besides assistant editor?” An assistant editor does not get on the plane and go to Detroit. I said, “I want to have a credit as associate director.” It should be noted that there was only one female associate director at NET the entire seven years that I was working there. One. Yet, I said, “I want to be in the credit as an associate director, and I want pay as an assistant editor, and a little bit above.” They agreed to my terms. When I got to Detroit I learned the white male crew had insulted the women. I helped mediate between the women and the film crew in order to finish the film. When my family and I sat down to watch the broadcast my kid says, “Look at the TV, Mommy. Mommy’s going to get a credit.” As associate director appears we see, in tiny letters, “Associate Director – Madeline Anderson”. You could hardly see it. The kids said, “Mommy, where’s your name?” But it was there. Barely, but I got it, and I had another voice at WNET.

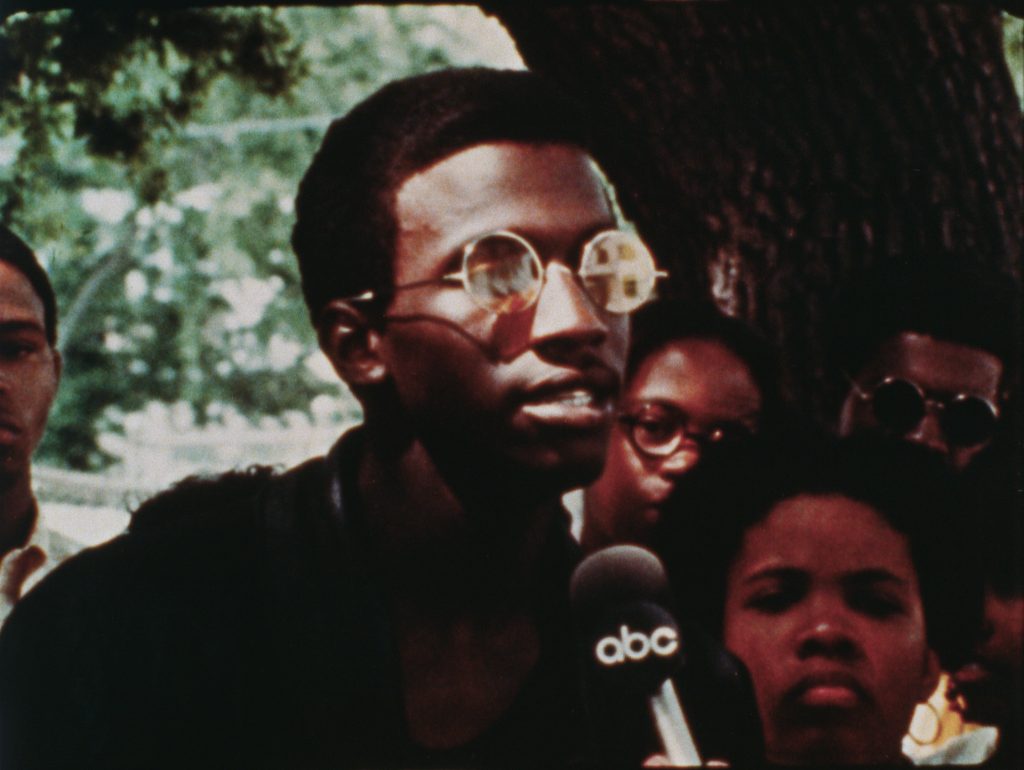

RC: Can you tell me about your experience working with Williams Greaves and Black Journal?

MA: I was at NET before many of the crew of Black Journal, which is a story within itself. But after Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, NET finally woke up to black programming. The executives realized there was an audience. I should add there was also this sense that maybe black programming would calm the community, since there was a lot of anger and hostility at the time.

The Ford Foundation funded programs all over the country and the series that they funded at NET was Black Journal. Initially it started out with a white executive producer, and then the production crew protested because it was supposed to be for, by, and about black experiences. It was around this time that Bill Greaves was hired. I wasn’t on the Black Journal staff then, but eventually came on board and worked on Black Journal.

RC: Why did you want to work on Black Journal?

MA: I wanted to work on Black Journal because it was a continuation of what I always wanted to do. I also saw it as an opportunity for black people to get into broadcasting. Thirdly, I believed in the messages that we took to our targeted audiences. Black people needed to know what was going on, not only in our world, but throughout the world; because as it was, a lot of us did not know about the struggle other black people were participating in all over the world.

RC: Can you explain how you came to produce A Tribute to Malcolm X for Black Journal?

MA: When I worked on Black Journal I was hired as an editor, but I would also try to get a chance to produce something. Even though I was an editor, I saw myself as a producer and from an early age I had imagined I would create a series about black progress, which is why created Integration Report 1. I imagined there would be an Integration Report 2, 3, 4. So people in the field knew I was a filmmaker, not just an editor, and that served me well because Bill Greaves [the executive producer for Black Journal,] would let me make short films. I would make ‘tribute films.’ I did a tribute film on Martin Luther King, Jr., which is lost. I have no idea where that film is. Often my short films would connect segments to the overall Black Journal program.

RC: Why a tribute film on Malcolm X?

MA: My husband and I were very political. I was a community activist, for instance my husband and I started a food co-op in our local church; we did a lot of things around the community, so when I worked with Shirley Clark on The Cool World, I met Malcolm X. Shirley was coming under scrutiny for the film so she invited different community organizations to come watch the film and provide feedback. Malcolm X was someone she invited and he came with some members of the Fruit of Islam.

Malcolm X was such a strong personality. He looked so good. He was perfectly groomed, and a clear, concise speaker. I was not only blown away by his personality, but his philosophies, so after he was killed I wanted to create a tribute to him. Bill Greaves knew Dr. Shabazz and that is how I got the chance to make the film. She did not trust anyone and was very protective of his [Malcolm X’s] legacy.

When I made the film, we had a very small budget. I only had a budget to get a cameraman, I was the soundman and I only had one day to shoot with one 400 foot roll of film. I interviewed Dr. Shabazz and then I went back and looked at the film, created a script from the interview, and then found newsreel footage from the Greenberg film library to intercut in the 10-minute piece.

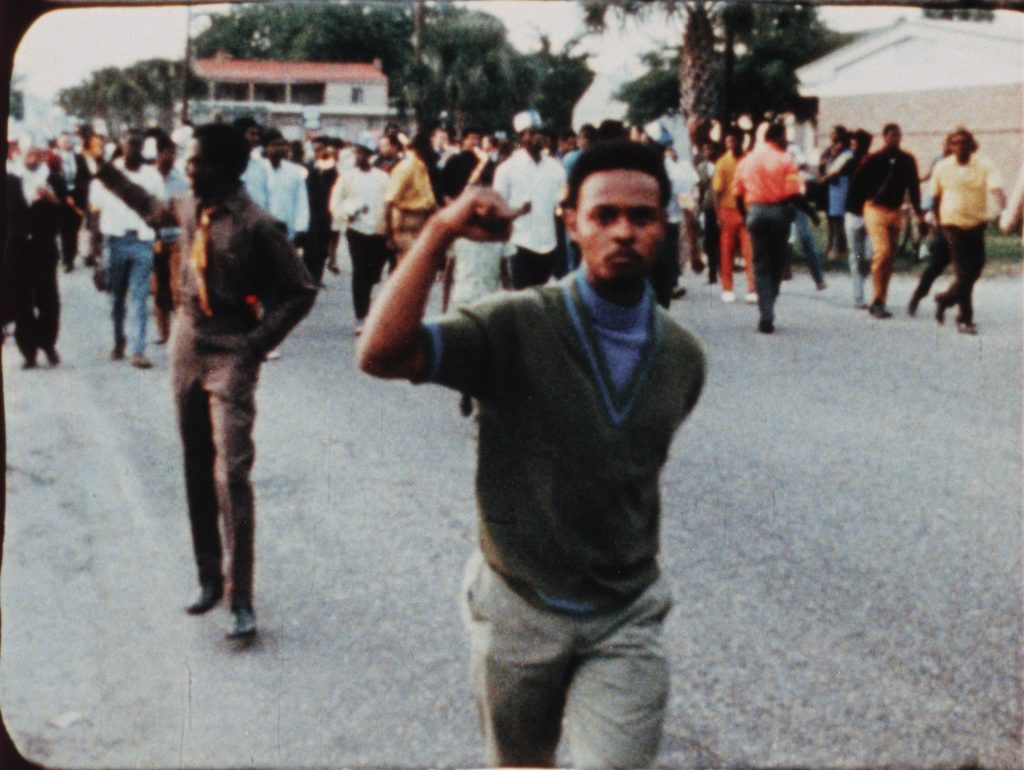

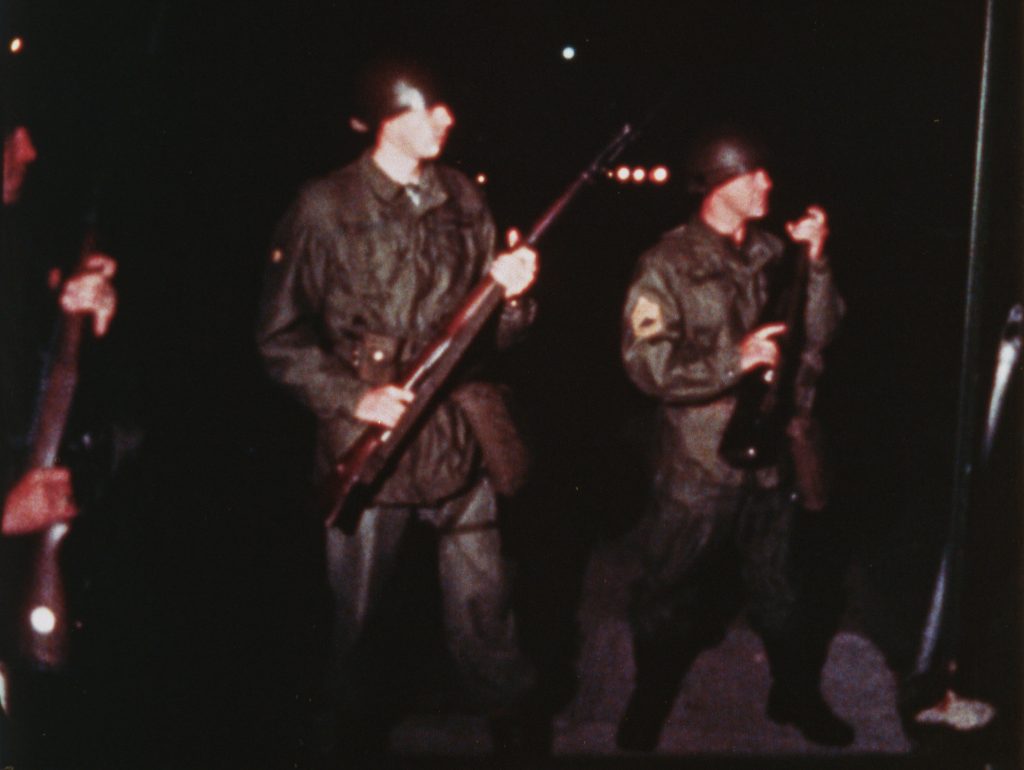

RC: Describe how and why you developed I Am Somebody.

MA: Well, it was the end of the first iteration of Black Journal. Bill was leaving as executive producer. A new executive producer was coming in and I felt that this was the time to move on. I had been at NET as an editor and then moved over to Black Journal as a senior editor. With Bill Greaves as Executive Producer, I produced and directed A Tribute to Malcolm X, along with a few other smaller pieces that were used to enrich the program. Although I didn’t get credit for it, I did it and was credited as an editor. It felt like it was time to move on to other things. Prior to leaving the company, I was doing research and going into film libraries looking for stock footage about the hospital protesters in South Carolina. The local chapter of the 1199, the Drug and Hospital Workers Union, found out I wanted to make this film and offered me money to make the film. It was just such a wonderful thing. This was also the first time I made a film where I had sufficient funds to do what I wanted to do. Since the strike had started before I got down there, I went to several film libraries where people knew me. I told them what I was going to do, and they saved me choice footage; then I got funding and a crew and I went to Charleston.

RC: How long did you stay on location?

MA: Well, I found out I was pregnant with my fourth child about a month before getting the funding for the film so I had to think about how long to be on location. We stayed for a week and a half.

RC: Your shot selection and storytelling feels as if this was a very familiar story for you.

MA: Even before traveling to South Carolina, I had already identified so much with these women. They were sisters. I knew them. They were up against gender, race, politics—the same things I had to overcome. I knew their story; it was just in a different setting, but I knew their story and I related to them in that way. I understood them. They were just so courageous.

Like the narrator, Claire Brown, she reminded me so much of myself. She’s a little woman. She had a very supportive husband. She had children. She was so earnest and determined. She was a leader. She knew how to express things and say things in few words. After I got the film together, I told the leadership of the Local 1199 that I wanted Claire to come up to New York and narrate the film. Claire came to New York and we had about four or five sessions in the studio where I would show her the film footage and record her reflections. I didn’t want a voice out of nowhere talking. I wanted somebody that felt it.

RC: What did this experience teach you?

MA: I learned about sisterhood for number one. That we’re all sisters. And we all go through the same experiences of being black women on one level or another, but we all go through it. Whether we want to admit it or not, we all go through it. Sad thing about it is we’re still going through it.

RC: You mention how others were instrumental in your career path. Did you help anyone get into a union?

MA: What I did was that when I got into a position where I could hire someone, I made sure that women were on the crew. I worked with a Chinese woman that was one of the first women into the cameraman’s union. I always worked with minority crewmembers. I was in tune with what women were trying to do and I helped by making sure that women were in the crew, and that minorities were in the crew.

RC: Was there anything else you learned about yourself as one of the first black female filmmakers and union editors?

MA: Well, I learned, all through my career. I had a sense of who I was, and I always acted that way. I respected myself and I respected other people. And I expected them to respect me. Now, I also had a partner that was my husband and I would not have been able to do what I did, a mother with four children, traveling all over the world, without a supportive partner. Never. My husband was so supportive of everything that I did. I didn’t have sexual harassment because every time I got a new job my husband would come to the job. Immediately everybody would know, “Oh, that’s Madeline’s husband.” There was no sexual harassment ever. Ever.

RC: Speaking of going through things, what would you say to young filmmakers today?

MA: Well, the first thing I would say that a lot of young people don’t want to hear is learn your craft, because learning my craft took me so many places. It took me all over the world. I wasn’t just a documentary filmmaker. I landed in places that I would never think I’d be. So, learn your craft. Choose what you want to do, and then go get it. Don’t let anything stand in your way.

This interview originally appeared in the Icarus Films DVD release I Am Somebody: Three Films by Madeline Anderson.

Leave a Reply