On Respecting Your Subject: An Interview with Jethro Waters

An interview between Priscilla Posada and filmmaker Jethro Waters.

“This was going to be a great film, because I had just met the most incredible subject.”

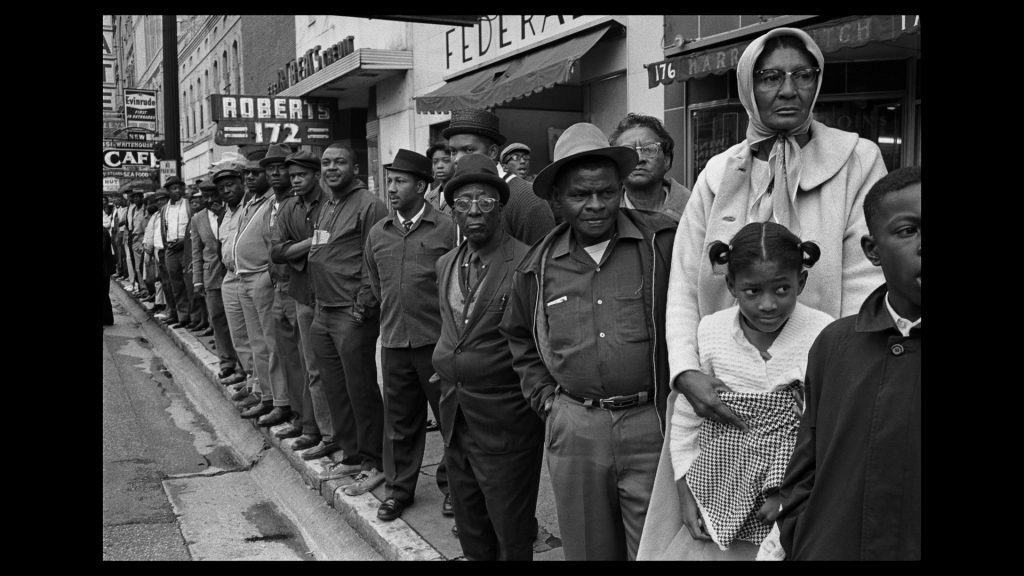

Filmmaker Jethro Waters has a background in cinematography and an ear for music. He tackles the biopic of master photographer Burk Uzzle without ever making you feel like you’re doing homework. There is energy in his work and a true respect for his subject. Though it’s hard to witness how little America has progressed in terms of racial justice since Uzzle began working seven decades ago, the film vibrates with hope that good things might yet still come. We sat down over Zoom to discuss his film F11 and Be There and some of the influences that contributed to its creation.

Let’s start at the very beginning. What was your inspiration for the title “F11 and Be There”?

Burk and I were in a car randomly talking about some famous people he’s photographed. He mentioned Robin Williams, and how it was such a funny shoot. Basically Williams was very nonchalant when he wasn’t in performance mode. He asked Burk to let him know when he was ready to go. And, the moment Burk said, “All right, let’s do this.” Williams just riffed off jokes and jumped around the room doing the craziest things Burk had ever seen for 45 minutes straight. And then as soon as Burk said, “That’s it, we’ve got it,” Williams shut off and was like, “It was great working with you guys” and was out the door.

Burk just says “Yeah, it was just one of the things that turned out great. It was F11 and be there.” I had never heard that and it just kind of took me by surprise. So I said, “What did you say?” And he said, “F11 and be there, you know?” It sounded beautiful, because F11 is an aperture setting on a camera and the “be there” part means putting yourself in the right moment at the right time. It’s both a technical and philosophical statement that speaks to work ethic as well.

Growing up, did you have a desire to become a filmmaker? What has your path there been like?

For as long as I can remember, it’s always been my dream to be a film director and a screenwriter. I grew up watching every action film out there with my dad. But for a while I just assumed that everything that I watched on TV was real and I remember always being so terrified for the good guys.

When I was six or seven, I think that’s when I understood that there was a camera involved in movies. And remember clearly asking my dad how this person, the cameraperson, stayed safe in a battle scene, with machine guns going off everywhere. My dad looked at me, laughed, and the realization came over him that I thought everything we were watching was real.

He paused the movie to explain exactly what was happening, how movies worked. From that moment forward, I remember thinking “Okay, that’s what I want to do.” I began taking photographs, writing, making stop-motion animations, and making films from a pretty early age, always intending to go to film school. Film school never happened, but the passion always remained.

I’d gone back to college in my late twenties for International Studies. That’s when I committed to making my first real film, which I made while studying abroad in Lisbon, Portugal. I had been editing and making my own personal films for quite some time, more experiments in editing and cinematography than anything. So it just dawned on me that it was time to make a real film, a documentary, and see if I could do this thing I had always wanted to do. And everything came together: it started with that documentary short, then short narrative films, music videos, film festivals, and it’s continued evolving from there.

How did you come across Burk Uzzle and what drew you to him as the subject of a documentary?

A producer that had previously reached out to me about working together connected me to Burk. And so I googled “Burk Uzzle.” Like most people do, I just shook my head, “Okay, I know all of this work.”

So we met for the first time at the Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill, North Carolina on September 11, 2016. I was meeting this guy, a legend, but he was so humble, and so kind. And I remember, within the first 10 minutes of talking to him, thinking to myself, “All I have to do is show up and make sure I have enough battery. And this film will make itself.”

He started explaining what he believes about civil rights, about social justice, about America, about the power of art. So that’s when I really knew that this was going to be a great film, because I had just met the most incredible subject.

From the film, it’s apparent that Burk takes a lot of inspiration from paintings. Which artists or mediums have most inspired your own work?

A lot of what’s really inspired me as a filmmaker comes from writers and poets. I’m inspired by the form and structure of poems, how simple they seem as you read them, but how they possess this infinite possibility for interpretation and reinterpretation. I try to orchestrate my films like poems, or collections of poems, rather than just your typical linear three-act story. I’m a huge fan of Fernando Pessoa, Toni Morrison, Billy Collins, Chimamanda Adichie—her novels are phenomenal. One of my favorites by her is Purple Hibiscus.

In terms of documentary filmmakers that I admire, I love films that serve both as complex works of art, cinematically or stylistically, while also conveying a very clear story. If you look at Errol Morris, William Greaves, Werner Herzog, Agnes Varda, or Ross McElwee, a lot of their documentary films are just extraordinary in this way.

“A lot of what I try and accomplish in films is to lean into orchestrating them like poems, or collections of poems, rather than just your typical linear three-act story.”

For people not familiar with the work of Burk Uzzle, how would you describe what makes a photograph of his, a Burk Uzzle photograph?

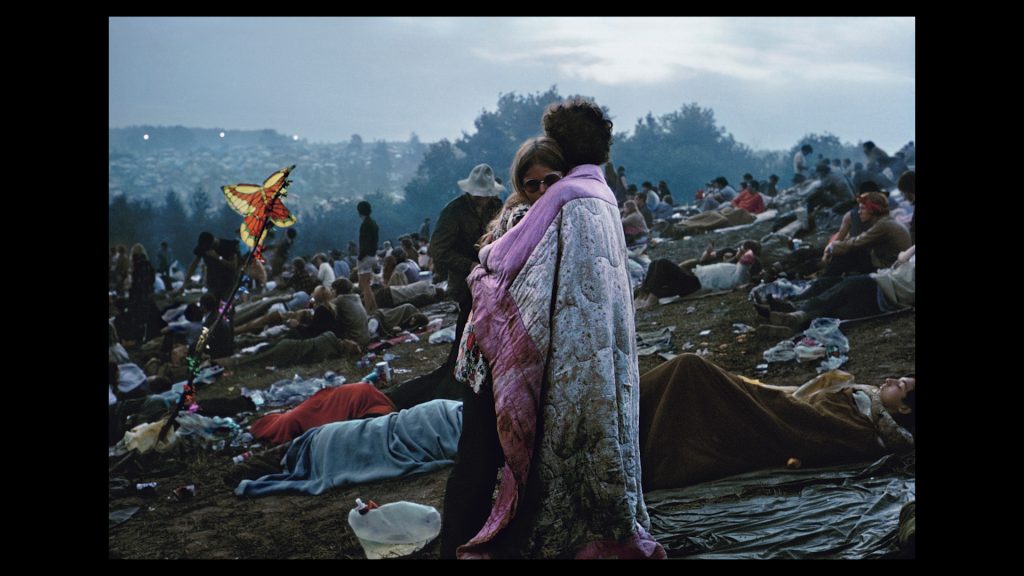

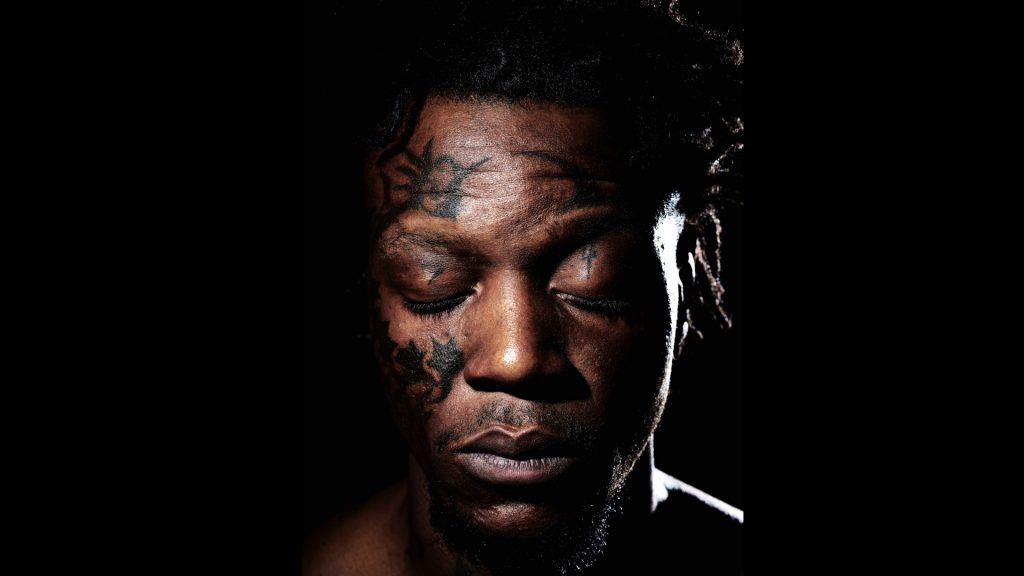

What makes Burk such a special artist and photographer is his range. He is so capable of anything and everything photographically. He has such a wonderful and eternal curiosity, this ability to find aesthetic interest in the seemingly smallest things and makes them into really beautiful works of art. He’s gone from photographing protests, landscapes, wars, Martin Luther King Jr., Woodstock, and then you turn the corner and he’s done an entire museum collection of tiny objects that were burnt in a house fire. His whole archive is that way, every corner you turn you’ll find some of the most stunningly beautiful pictures ever made, covering the most diverse range of subject matter, done in all manner of styles. His work is so striking because it’s so interesting and so diverse.

“One of the most important lessons I’ve learned from Burk is that it all comes down to respecting your subject, no matter what.”

Burk Uzzle’s career spans seven decades. What have you learned from him that has changed the way you view your own artistic path or life in general?

He started when he was 12 years old, photographing for the local newspaper. So that would have been around 1950. When you’re already starting out as a really good, instinctual photographer like Burk was at that age and then you go on to work with Cornell Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson, what more is there? Something Burk talks about, and exemplifies with his life, is the power of art to do social good. Art can tell the truth.

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned from Burk is that it all comes down to respecting your subject, no matter what. Whether you agree or disagree with what’s being said, what is being represented, respect is so important. And it’s not just about who you’re photographing or filming, you know, it’s so much more than that. Just respecting the person next to you. Acknowledging and honoring the humanity in everyone, that is something the world desperately needs more of.

Jethro’s favorite film on OVID is Ross McElwee’s documentary SHERMAN’S MARCH.

Watch F11 AND BE THERE on OVID.