A. S. Hamrah Selects

Ovid asked me to recommend a selection of films streaming on their channel. Initially attracted by the documentaries they offer about musicians I love, including Ornette Coleman, Pulp, Bill Callahan, and the Magnetic Fields, instead I picked ten features that are not music docs.

Nevertheless, I do have to recommend Joe Angio’s Revenge of the Mekons (2013), because everyone should hear the story of the night in the late 1970s in Dublin when U2 opened for the great punk socialists and told them U2 was going to be bigger than they would ever be. They were right! But so wrong.

Now, here are ten films (in reverse chronological order) you can see that are better than the one showing with U2 at the Sphere, and you don’t have to go to Las Vegas to see them.

— A. S. HAMRAH

Reason, Parts 1 & 2 (Anand Patwardhan, 2018)

A chronicle of beatings and homicides associated with India’s ruling party, the fundamentalist, anti-rational BJP, this documentary exposes how religious absolutism sanctions violence and silences dissent. Patwardhan gathers material from recent news, presenting the vicious zeal around construction of the Ram Mandir, a massive Hindu temple built over the ruins of a sixteenth-century mosque. Given the aggression on display in Reason, it was surprising to learn one of Hindu nationalism’s foundational texts is a book called Bunch of Thoughts. A documentary hero whose practice has become riskier since the rise of his exact contemporary Narendra Modi, Patwardhan has made seventeen films since 1971, and continues despite bans and death threats.

Hanagatami (Nobuhiko Ōbayashi, 2017)

A heartbreaking dissection of Japanese nationalism set on the eve of World War II, this melodrama from the director of House (1977) is the third of four movies from his final period, a wild, late flowering that began in 2012 with Casting Blossoms to the Sky and continued through his final testament, the crazy epic Labyrinth of Cinema (2019). Ōbayashi uses computer-generated effects with an abandon unseen in more naturalistic films, a simultaneous revel in digital artifice and a justification for its existence. He created a dizzying world that, in Hanagatami, reflects the fraught psychology of his teenage characters, several of whom look forty years old. As their country slides into war, they decline into tragic perversities, including delicate vampirism and homoerotic midnight nude horseback rides on the beach, presented by Ōbayashi as if he is making a film out of Archie comics.

Nobuhiko Ōbayashi’s War Trilogy is here

Little Sister (Zach Clark, 2016)

A novitiate (Addison Timlin) leaves her convent in Brooklyn, traveling to her family’s house in suburban North Carolina to visit her brother (Keith Poulson), a veteran recently returned from the war in Iraq with severe burns that have eradicated his face. The title is a pun: Colleen, a former goth teen, is Jacob’s younger sister and a fledgling nun. Set in 2008, during the economic collapse and the Obama-McCain election, the film is a look back at a terrible time. Poised on the outer reaches of discomfort familiar from the work of Mike Leigh and Todd Solondz, Clark’s film could have been called The Worst Years of Our Lives, if the times and our lives hadn’t gotten worse. That Little Sister is also set the week of Halloween lends an uncanny vibe to this family drama of masks. Everybody here dons costumes to better enact their dysfunction, as they scarf down edibles in front of straight-arrow Colleen, who has to decide whether to leave again for the church, where the rituals are less chaotic and Jesus provides a cocoon.

Little Feet (Alexandre Rockwell, 2013)

Alexandre Rockwell may be the most underrated filmmaker of the 1990s indie generation that includes Tarantino and Soderbergh. He’s even more underrated than Allison Anders. For the last decade or so he has been making simple-seeming, neo-neorealist films, in black-and-white with splotches of color, featuring his family, especially his biracial daughter, Lana Rockwell, who is a natural actress and great screen presence. The films, set in Los Angeles and Brockton, Massachusetts, are among the few made that show urban poverty for what it is, that portray messed-up parents without sentimentality, and that have a mature, subtle view of the dangers of race in America. Little Feet, from 2013, combines De Sica with the photographs of Ralph Meatyard to create a Little Rascals for the 2010s, and was maybe too arty or not political enough or made by a filmmaker who wasn’t the right age for the times. 2021’s Sweet Thing is just as good and suffered the same fate.

Almayer’s Folly (Chantal Akerman, 2011)

Akerman’s penultimate film, based on Joseph Conrad’s first novel but set not in late 19th-century Borneo but in the Malaysia of the (I think) early 1960s, did not get a proper US release, didn’t get great reviews, and was ignored by audiences, especially compared to her more personal documentary, No Home Movie (2015), the last film she completed before her death. Perhaps the unjust failure of this ambitious masterpiece had closed off a certain kind of filmmaking to her. Almayer’s Folly should be reevaluated. While the times have not quite caught up with its languors and its deceptive deconstructions of colonialism and patriarchy, I see its influence in less accomplished movies like Albert Serra’s Pacifiction (2022) and lots of other, shorter works by less determined filmmakers. Starring Stanislas Merhar, the lead in Akerman’s Proust adaptation, La Captive (2000), and Aurora Marion as his mixed-race daughter, and shot on location, this film starts where something like The Passenger (1975) left off. The first shot is like the last one in Antonioni’s film, yet Akerman’s is more virtuosic, has more actors in it, she had the guts to break it up, and it happens during a live karaoke performance of Dean Martin’s “Sway.”

Crimson Gold (Jafar Panahi, 2003)

Another film lost in the cracks, maybe because it sits uncomfortably between other works by its two creators, Jafar Panahi, who directed it, and Abbas Kiarostami, who wrote it, and is more obvious in its violence than their other films. Crimson Gold is kind of an Iranian Taxi Driver (1976), with a lead non-actor (Hossain Emadeddin) playing a version of himself, a veteran of the Iran-Iraq war who works on a scooter as a pizza delivery man and who suffers from war-related ailments: pain that he manages with cortisone that bloats him, and psychological issues that seem untreated and that make him logy and disconnected. Working as a delivery man exposes Emadeddin to Tehran’s wealthy, and to their cop protectors, who treat him with various degrees of disrespect, indifference, and condescension. Tired of poverty and low-wage work, he and a buddy turn to smash-and-grab jewel robbery in this movie based, like Kiarostami’s Closeup (1990) and Panahi’s The Circle (2000), on a story they found in the news.

Time Regained (Raúl Ruiz, 1999)

Ruiz’s Proust adaptation is maximal where Akerman’s is minimal. In its dedication to subtle illusionist cinematic trickery used to evoke memory, it has things in common with Ōbayashi’s work. But Ruiz, unlike the director of Hanagatami, eschews all digital effects and insists on doing everything in front of the camera. This makes Time Regained a testament to twentieth-century cinema as much as to the twentieth-century literary masterpiece it’s based on. And like in Hanagatami, this film is war-haunted, inserting black-and-white World War I scenes into its golden Parisian salons, as Marcel (Marcello Mazzarella, his voiced dubbed by Patrice Chereau) glides through these spaces, sometimes on unseen dolly tracks and cranes. Ruiz uses every device, every camera move, and every bit of studio stagecraft in this film, the best Proust movie and the only one to confront its text head on and solve the problem of reproducing the interiority of Proust’s flashback structure on screen. It’s unlikely anything like it will ever be attempted again. With a who’s-who cast of French actors (and John Malkovich), Time Regained bookends Proust’s century with a mystery and beauty all its own.

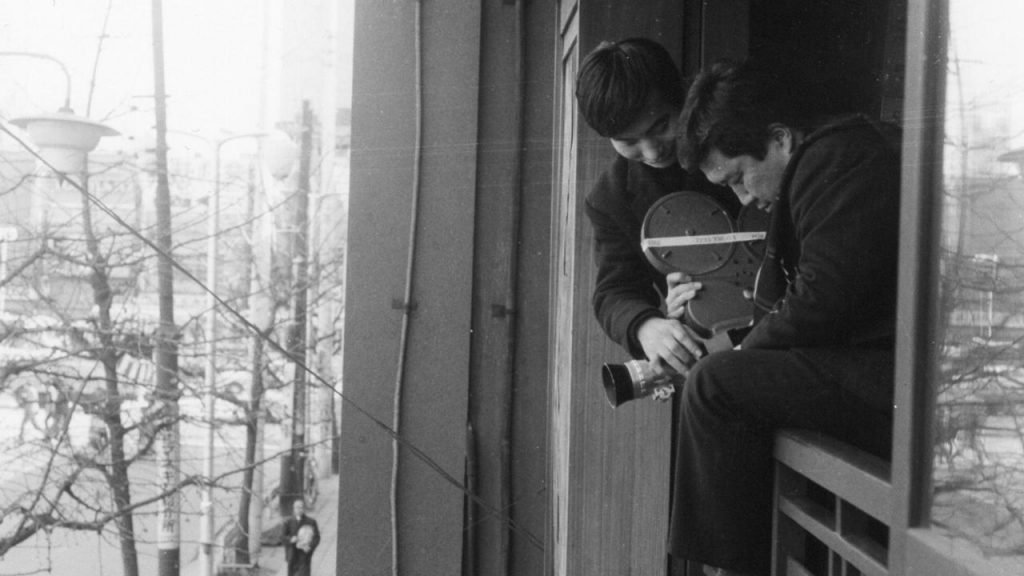

The Last Bolshevik (Chris Marker, 1992)

Marker’s documentary about the Soviet filmmaker Aleksandr Medvedkin, released shortly after Medvedkin’s death, frames a career in film directing under Stalin as a series of dangerous compromises, sometimes highlighted by moments of innovation, artistic success, and glory; other times, by a trip to the gulag. Marker, as he often does, presents the film as a letter, “writing” it to Medvedkin as a summation of their friendship and elegy for Medvedkin’s work—the documentaries he made on his Cinetrain studio and lab that moved through the Russian countryside filming and cutting short documentaries about farm and factory workers, and the anarchic comedy Happiness (1935), a feature-length satire that got him into trouble. Marker of course takes time to relate Medvedkin’s life in the Soviet Union to his own movements through the century. We learn that he was in Times Square in New York with the blind composer and street musician Moondog, “the Viking of Sixth Avenue,” on the night Stalin died, which Marker learned about from the moving news ticker above the illuminated billboards and presumably read to Moondog as it zipped by.

Watch The Last Bolshevik on OVID

Le Crabe-Tambour (Pierre Schoendoerffer, 1977)

Schoendoerffer was a newsreel cameraman during the French Indochina War who became a novelist and then a director of gritty war movies, both narrative features and documentaries. In the US he is perhaps most known for The Anderson Platoon, a 1967 doc about a US Army platoon fighting in Vietnam under the command of a Black lieutenant. His frequent cinematographer was Raoul Coutard, ace DP of the French New Wave, who shot many films for Jean-Luc Godard. Coutard was also in the French war in Vietnam and it was through Schoendoerffer that he became a cinematographer. Le Crabe-Tambour is a post-war maritime film that looks like a documentary and an art film. The film has a Conradian quality (someone in fact reads a Conrad novel in it) and would make a good companion piece to Almayer’s Folly. Here, two French naval officers (Jean Rochefort and Claude Rich) serving in the North Atlantic reminisce about a third (Jacques Perrin), now in disrepute and serving on a commercial trawler they’re due to encounter in the icy water. A blood-red, almost abstract map of France hangs in the ship’s captain’s quarters, and the film inhabits the vast landscape and seascape of midcentury French militarism, alternating between snow and sunshine, moving from Vietnam to Newfoundland and from Algeria to Brittany. A haunted interrogation of naval life, Le Crabe-Tambour comes close to predicting the Claire Denis films of twenty years later, though it’s harder and less ethereal.

Watch Le Crabe-Tambour on OVID

A Man Vanishes (Shôhei Imamura, 1967)

Every year in Japan a certain number of people go johatsu—without notice they leave their lives, families, and jobs, and disappear, without telling anyone, into an internal exile, under a new name in another part of the country. Imamura’s documentary about one such man, shot in cheap-looking, grainy black-and-and white, gathers together the man’s friends, relatives, and co-workers, interviewing them where they work and live and in places where they interacted with the missing man. They compete for the filmmaker’s attention, especially the man’s deserted fiancée, and as the film progresses the story gets thornier and more complicated, bogged down in detail. It becomes easy to see why someone would want to get away from all this, the this being the minutia of life, its complications, its quotidian nothingness. Near the end, Imamura goes meta, revealing that A Man Vanishes is some kind of set-up, declaring it a fiction that is ended, then reminding us that “reality is not over.” Excuse me while I disappear.

A. S. Hamrah’s work has appeared in many publications, including Bookforum, Harper’s, n+1, and The New York Review of Books. A collection of his work, The Earth Dies Streaming: Film Writing, 2002–2018 (n+1 Books), was called “essential reading” by The Nation and “form-bending, disobedient” by New York magazine.

Anonymous

I knew none of these titles, so thanks for expanding my horizons (once again), A.S. Harmrah.